contact: philippa@pilotopardo.com

Eat the Roses

Darya Diamond

Opening: 7 November, 6–8 pm

8 November 2025–10 January 2026

The image of the breastfeeding Madonna, or Madonna Lactans, is a recurring motif in ecclesiastical depictions of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus. Often portrayed with one breast in the child’s mouth, these iconographic scenes present the Madonna as a nurturing mother nourishing, protecting, and embodying divine procreation. There is a legend surrounding La Madonna (Lacunas) in which St. Bernard of Clairvaux prays before a statue of the Madonna in 1146, and was said to have received a miraculous stream of her milk into his mouth; granting him wisdom, or in some versions, curing his illness. Images of La Madonna with her breasts in hand have percolated from that tale in various forms throughout history.

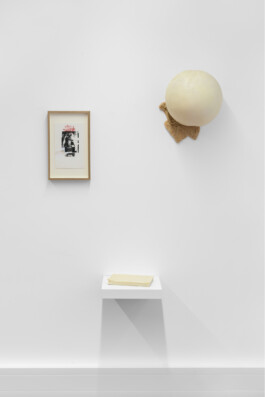

In 5–7 Excelsior Works (2025), a series of block prints and screen prints echoes imagery sourced from the artist featured in pornography, as well as imagery of La Madonna Lactans and La Santa Muerte, printed on a duvet. In these prints, Diamond reinterprets La Madonna’s sacred gesture through a lens of self-representation, pleasure, and labour. The economy of divinity becomes personal and bodily; the artist herself appears in a pornographic scene next to the Madonna, in which a client is sucking her nipples. We see a gesture that echoes St. Bernard’s miraculous renewal, charged with erotic intensity of oral pleasure. True to form, Diamond is blending boundaries between the sacred and the profane.

Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia defines spaces that are constantly redefined by their content. Diamond frames the bedroom or the hotel room as a heterotopic site where care, fantasy, and labor take place. She often references the ‘girlfriend experience’, a sector of full-service sex work that encompasses emotional intimacy as well as sexual labor. Like the image of the Madonna referenced in her prints, the sex worker performs and nurtures. Her encounters with clients are never the same, as they are constantly shaped and re-shaped by her counterparts needs and the settings they inhabit. Like the hotels and bedrooms she works in the sex worker herself becomes a heterotopia - constantly redefined by the desires of her clients while cultivating attention and care in in order to provide whatever remedial comfort they need. She is a mirror, an anonymous sanctuary, and a sexual sanctum.

For this exhibition Diamond expands these ideas beyond print into a sculptural installation, recreating the standardised intimacy of the hotel or motel room: lamps cast in soap, a bible, a carpet. Her work meditates on labor, pleasure, sex, and emotional support. The exhibition space becomes a site of recontextualization, a mutable framework reflecting the ever- shifting environments that shape sex work. Diamond’s practice, grounded in an ethos of care, transforms the obscured realms of sexual and domestic labor into a compelling visual narrative, one that fuses the restorative and psychosexual, the therapeutic and erotic, and ultimately questioning the distinction between site and stage.

Darya Diamond is a Mexican-American artist based in London. She graduated from her MFA at Goldsmiths, University of London in 2020, and holds a BA from Hampshire College, MA. Her practice intersects across mediums such as sculpture, audio, print and film. Her practice is ritually and theoretically rooted in methods of reproduction – regenerating and renegotiating the promise of transactional intimacy, care, and invisible labour. Her work has been recently exhibited in Los Angeles (Sebastian Gladstone Gallery), Naples (Pu-Teca), London (Import Export, Pippy Houldsworth, Guts Projects, Zabludowicz), Paris (Pauline Perplexe), among others. This is her third exhibition with piloto pardo and the third exhibition at the gallery's new permanent space.